Tokio is a Rust framework for developing

applications which perform asynchronous I/O — an event-driven

approach that can often achieve better scalability, performance, and

resource usage than conventional synchronous I/O. Unfortunately, Tokio

is notoriously difficult to learn due to its sophisticated abstractions.

Even after reading the tutorials, I didn't feel that I had internalized

the abstractions sufficiently to be able to reason about what was

actually happening.

My prior experience with asynchronous I/O programming may have even

hindered my Tokio education. I'm accustomed to using the operating

system's selection facility (e.g. Linux epoll) as a starting point, and

then moving on to dispatch, state machines, and so forth. Starting with

the Tokio abstractions with no clear insight into where and how the

underlying epoll_wait() happens, I found it difficult to

connect all the dots. Tokio and its future-driven approach felt like

something of a black box.

Instead of continuing on a top-down approach to learning Tokio, I

decided to instead take a bottom-up approach by studying the source code

to understand exactly how the current concrete implementation drives the

progression from epoll events to I/O consumption within a

Future::poll(). I won't go into great detail about the

high-level usage of Tokio and futures, as that is better covered in the

existing

tutorials. I'm also not going to discuss the general problem of

asynchronous I/O beyond a short summary, since entire books could be

written on the subject. My goal is simply to have some confidence that

futures and Tokio's polling work the way I expect.

First, some important disclaimers. Note that Tokio is actively being

developed, so some of the observations here may quickly become

out-of-date. For the purposes of this study, I used tokio-core

0.1.10, futures 0.1.17, and mio 0.6.10.

Since I wanted to understand Tokio at its lowest levels, I did not

consider higher-level crates like tokio-proto and

tokio-service. The tokio-core event system itself has a

lot of moving pieces, most of which I avoid discussing in the interest

of brevity. I studied Tokio on a Linux system, and some of the

discussion necessarily touches on platform-dependent implementation

details such as epoll. Finally, everything mentioned here is my

interpretation as a newcomer to Tokio, so there could be errors or

misunderstandings.

Asynchronous I/O in a nutshell

Synchronous I/O programming involves performing I/O operations which

block until completion. Reads will block until data arrives, and writes

will block until the outgoing bytes can be delivered to the kernel.

This fits nicely with conventional imperative programming, where a

series of steps are executed one after the other. For example, consider

an HTTP server that spawns a new thread for each connection. On this

thread, it may read bytes until an entire request is received (blocking

as needed until all bytes arrive), processes the request, and then write

the response (blocking as needed until all bytes are written).

This is a very straightforward approach.

The downside is that a distinct thread is needed for each

connection due to the blocking, each with its own stack. In many cases

this is fine, and synchronous I/O is the correct approach. However, the

thread overhead hinders scalability on servers trying to handle a very

large number of connections (see: the C10k problem),

and may also be excessive on low-resource systems handling a few

connections.

If our HTTP server was written to use asynchronous I/O, on the other

hand, it might perform all I/O processing on a single thread. All

active connections and the listening socket would be configured as

non-blocking, monitored for read/write readiness in an event loop, and

execution would be dispatched to handlers as events occur. State and

buffers would need to be maintained for each connection. If a handler

is only able to read 100 bytes of a 200-byte request, it cannot wait for

the remaining bytes to arrive, since doing so would prevent other

connections from making progress. It must instead store the partial

read in a buffer, keep the state set to "reading request", and return to

the event loop. The next time the handler is called for this

connection, it may read the remainder of the request and transition to a

"writing response" state. Implementing such a system can become hairy

very fast, with complex state machines and error-prone resource

management.

The ideal asynchronous I/O framework would provide a means of writing

such I/O processing steps one after the other, as if they were blocking,

but behind the scenes generate an event loop and state machines. That's

a tough goal in most languages, but Tokio brings us pretty close.

The Tokio stack

The Tokio stack consists of the following components:

-

The system selector.

Each operating system provides a facility for receiving I/O events, such

as epoll (Linux),

kqueue() (FreeBSD/Mac OS), or IOCP

(Windows).

-

Mio - Metal I/O.

Mio is a Rust crate that

provides a common API for low-level I/O by internally handling the

specific details for each operating system. Mio deals with the

specifics of each operating system's selector so you don't have to.

-

Futures.

Futures provide a

powerful abstraction for representing things that have yet to happen.

These representations can be combined in useful ways to create composite

futures describing a complex sequence of events. This abstraction is

general enough to be used for many things besides I/O, but in Tokio we

develop our asynchronous I/O state machines as futures.

-

Tokio

The

tokio-core

crate provides the central event loop which integrates with Mio to

respond to I/O events, and drives futures to completion.

-

Your program.

A program using the Tokio framework can construct asynchronous I/O

systems as futures, and provide them to the Tokio event loop for

execution.

Mio: Metal I/O

Mio provides a low-level I/O API allowing callers to receive events such

as socket read/write readiness changes. The highlights are:

-

Poll and Evented.

Mio supplies the

Evented trait to represent anything that can be a source of

events. In your event loop, you register a number of

Evented's with a mio::Poll object, then call mio::Poll::poll() to block until events have occurred on one

or more Evented objects (or the specified timeout has

elapsed).

-

System selector.

Mio provides cross-platform access to the system selector, so that Linux

epoll, Windows IOCP, FreeBSD/Mac OS

kqueue(), and

potentially others can all be used with the same API. The overhead

required to adapt the system selector to the Mio API varies. Because

Mio provides a readiness-based API similar to Linux epoll, many parts of

the API can be one-to-one mappings when using Mio on Linux. (For

example, mio::Events essentially is an array of

struct epoll_event.) In contrast, because Windows IOCP is

completion-based instead of readiness-based, a bit more adaptation is

required to bridge the two paradigms. Mio supplies its own versions of

std::net structs such as TcpListener,

TcpStream, and UdpSocket. These wrap the

std::net versions, but default to non-blocking and provide

Evented implementations which add the socket to the system

selector.

-

Non-system events.

In addition to providing readiness of I/O sources, Mio can also indicate

readiness events generated in user-space. For example, if a worker

thread finishes a unit of work, it can signal completion to the event

loop thread. Your program calls

Registration::new2() to obtain a (Registration,

SetReadiness) pair. The Registration object is an

Evented which can be registered with Mio in your event

loop, and set_readiness() can be called on the

SetReadiness object whenever readiness needs to be

indicated. On Linux, non-system event notifications are implemented

using a pipe. When SetReadiness::set_readiness() is

called, a 0x01 byte is written to the pipe.

mio::Poll's underlying epoll is configured to monitor the

reading end of the pipe, so epoll_wait() will unblock and

Mio can deliver the event to the caller. Exactly one pipe is created

when Poll is instantiated, regardless of how many (if any)

non-system events are later registered.

Every Evented registration is associated with a

caller-provided usize value typed as mio::Token, and this value is returned with events to

indicate the corresponding registration. This maps nicely to the system

selector in the Linux case, since the token can be placed in the 64-bit

epoll_data union which functions in the same way.

To provide a concrete example of Mio operation, here's what happens

internally when we use Mio to monitor a UDP socket on a Linux system:

-

Create the socket.

123456

|

let socket = mio::net::UdpSocket::bind(

&SocketAddr::new(

std::net::IpAddr::V4(std::net::Ipv4Addr::new(127,0,0,1)),

2000

)

).unwrap();

|

This creates a Linux UDP socket, wrapped in a

std::net::UdpSocket, which itself is wrapped in a

mio::net::UdpSocket. The socket is set to be non-blocking.

-

Create the poll.

1

|

let poll = mio::Poll::new().unwrap();

|

Mio initializes the system selector, readiness queue (for non-system

events), and concurrency protection. The readiness queue initialization

creates a pipe so readiness can be signaled from user-space, and the

pipe's read file descriptor is added to the epoll. When a

Poll object is created, it is assigned a unique

selector_id from an incrementing counter.

-

Register the socket with the poll.

123456

|

poll.register(

&socket,

mio::Token(0),

mio::Ready::readable(),

mio::PollOpt::level()

).unwrap();

|

The UdpSocket's Evented.register() function is

called, which proxies to a contained EventedFd which adds

the socket's file descriptor to the poll selector (by ultimately using

epoll_ctl(fepd, EPOLL_CTL_ADD, fd, &epoll_event) where

epoll_event.data is set to the provided token value). When

a UdpSocket is registered, its selector_id is

set to the Poll's, thus associating it with the selector.

-

Call poll() in an event loop.

123456

|

loop {

poll.poll(&mut events, None).unwrap();

for event in &events {

handle_event(event);

}

}

|

The system selector (epoll_wait()) and then the readiness

queue are polled for new events. (The epoll_wait() blocks,

but because non-system events trigger epoll via the pipe in addition to

pushing to the readiness queue, they will still be processed in a timely

manner.) The combined set of events are made available to the caller

for processing.

Futures and Tasks

Futures

are techniques borrowed from functional programming whereby computation

that has yet to happen can be represented as a "future", and these

individual futures can be combined to develop complex systems. This is

useful for asynchronous I/O because the basic steps needed to perform

transactions can be modeled as such combined futures. In the HTTP

server example, one future may read a request by reading bytes as they

become available until the end of the request is reached, at which time

a "Request" object is yielded. Another future may process a request and

yield a response, and yet another future may write responses.

In Rust, futures are implemented in the futures crate. You

can define a future by implementing the Future trait, which requires a poll() method which is called as needed to allow the future

to make progress. This method returns either an error, an indication that the

future is still pending thus poll() should be called again

later, or a yielded value if the future has reached completion. The

Future trait also provides a great many combinators as

default methods.

To understand futures, it is crucial to understand tasks, executors, and

notifications — and how they arrange for a future's

poll() method to be called at the right time. Every future

is executed within a task context. A task itself is directly associated with

exactly one future, but this future may be a composite future that

drives many contained futures. (For example, multiple futures joined

into a single future using the join_all() combinator, or two futures executed in series

using the and_then() combinator.)

Tasks and their futures require an executor to run. An

executor is responsible for polling the task/future at the correct times

— usually when it has been notified that progress can be made.

Such a notification happens when some other code calls the notify() method of the provided object implementing the

futures::executor::Notify trait. An example of this can be

seen in the extremely simple executor provided by the

futures crate that is invoked when calling the wait() method on a future. From the source code:

233234235236237238239240241242243244245246247248249

|

/// Waits for the internal future to complete, blocking this thread's

/// execution until it does.

///

/// This function will call `poll_future` in a loop, waiting for the future

/// to complete. When a future cannot make progress it will use

/// `thread::park` to block the current thread.

pub fn wait_future(&mut self) -> Result<F::Item, F::Error> {

ThreadNotify::with_current(|notify| {

loop {

match self.poll_future_notify(notify, 0)? {

Async::NotReady => notify.park(),

Async::Ready(e) => return Ok(e),

}

}

})

}

|

Given a futures::executor::Spawn object previously created to fuse a

task and future, this executor calls poll_future_notify() in a loop. The provided

Notify object becomes part of the task context and the

future is polled. If a future's poll() returns

Async::NotReady indicating that the future is still

pending, it must arrange to be polled again in the future. It

can obtain a handle to its task via futures::task::current() and call the notify() method whenever the future can again make progress.

(Whenever a future is being polled, information about its associated

task is stored in a thread-local which can be accessed via

current().) In the above case, if the poll returns

Async::NotReady, the executor will block until the

notification is received. Perhaps the future starts some work on

another thread which will call notify() upon completion, or

perhaps the poll() itself calls notify()

directly before returning Async::NotReady. (The latter is

not common, since theoretically a poll() should continue

making progress, if possible, before returning.)

The Tokio event loop acts as a much more sophisticated executor that

integrates with Mio events to drive futures to completion. In this

case, a Mio event indicating socket readiness will result in a

notification that causes the corresponding future to be polled.

Tasks are the basic unit of execution when dealing with futures, and are

essentially green

threads providing a sort of cooperative

multitasking, allowing multiple execution contexts on one operating

system thread. When one task is unable to make progress, it will yield

the processor to other runnable tasks. It is important to understand

that notifications happen at the task level and not the future level.

When a task is notified, it will poll its top-level future, which may

result in any or all of the child futures (if present) being polled.

For example, if a task's top-level future is a join_all() of ten other futures, and one of these futures

arranges for the task to be notified, all ten futures will be polled

whether they need it or not.

Tokio's interface with Mio

Tokio converts task notifications into Mio events by using Mio's

"non-system events" feature described above. After obtaining a Mio

(Registration, SetReadiness) pair for the task, it

registers the Registration (which is an

Evented) with Mio's poll, then wraps the

SetReadiness object in a MySetReadiness which

implements the Notify trait. From the source code:

791792793794795796797798

|

struct MySetReadiness(mio::SetReadiness);

impl Notify for MySetReadiness {

fn notify(&self, _id: usize) {

self.0.set_readiness(mio::Ready::readable())

.expect("failed to set readiness");

}

}

|

In this way, task notifications are converted into Mio events, and can

be processed in Tokio's event handling and dispatch code along with

other types of Mio events.

Just as Mio wraps std::net structs such as

UdpSocket, TcpListener, and

TcpStream to customize functionality, Tokio also uses

composition and decoration to provide Tokio-aware versions of these

types. For example, Tokio's UdpSocket looks something like

this:

Tokio's versions of these I/O source types provide constructors that

require a handle to the event loop (tokio_core::reactor::Handle). When instantiated, these

types will register their sockets with the event loop's Mio poll to

receive edge-triggered events with a newly assigned even-numbered token.

(More on this, below.) Conveniently, these types will also arrange for

the current task to be notified of read/write readiness whenever the

underlying I/O operation returns WouldBlock.

Tokio registers several types of Evented's with Mio, keyed

to specific tokens:

-

Token 0 (TOKEN_MESSAGES) is used for Tokio's internal

message queue, which provides a means of removing I/O sources,

scheduling tasks to receive read/write readiness notifications,

configuring timeouts, and running arbitrary closures in the context of

the event loop. This can be used to safely communicate with the event

loop from other threads. For example, Remote::spawn() marshals the future to the event loop via

the message system.

The message queue is implemented as a futures::sync::mpsc stream. As a futures::stream::Stream (which is similar to a future,

except it yields a sequence of values instead of a single value), the

processing of this message queue is performed using the

MySetReadiness scheme mentioned above, where the

Registration is registered with the

TOKEN_MESSAGES token. When TOKEN_MESSAGES

events are received, they are dispatched to the

consume_queue() method for processing. (Source: enum Message, consume_queue())

-

Token 1 (TOKEN_FUTURE) is used to notify Tokio that the

main task needs to be polled. This happens when a notification occurs

which is associated with the main task. (In other

words, the future passed to Core::run() or a child thereof,

not a future running in a different task via spawn().) This

also uses a MySetReadiness scheme to translate future

notifications into Mio events. Before a future running in the main task

returns Async::NotReady, it will arrange for a notification

to be sent later in a manner of its choosing. When the resulting

TOKEN_FUTURE event is received, the Tokio event loop will

re-poll the main task.

-

Even-numbered tokens greater than 1 (TOKEN_START+key*2) are

used to indicate readiness changes on I/O sources. The key is the

Slab key for the associated Core::inner::io_dispatch

Slab<ScheduledIo> element. The Mio I/O source types

(UdpSocket, TcpListener, and

TcpStream) are registered with such a token automatically

when the corresponding Tokio I/O source types are instantiated.

-

Odd-numbered tokens greater than 1 (TOKEN_START+key*2+1)

are used to indicate that a spawned task (and thus its associated

future) should be polled. The key is the Slab key for the

associated Core::inner::task_dispatch

Slab<ScheduledTask> element. As with

TOKEN_MESSAGES and TOKEN_FUTURE events, these

also use the MySetReadiness plumbing.

Tokio event loop

Tokio, specifically tokio_core::reactor::Core, provides the event loop to manage

futures and tasks, drive futures to completion, and interface with Mio

so that I/O events will result in the correct tasks being notified.

Using the event loop involves instantiating the Core with

Core::new() and calling Core::run() with a single future. The event loop will drive

the provided future to completion before returning. For server

applications, this future is likely to be long-lived. It may, for

example, use a TcpListener to continuously accept new

incoming connections, each of which may be handled by their own future

running independently in a separate task created by Handle.spawn().

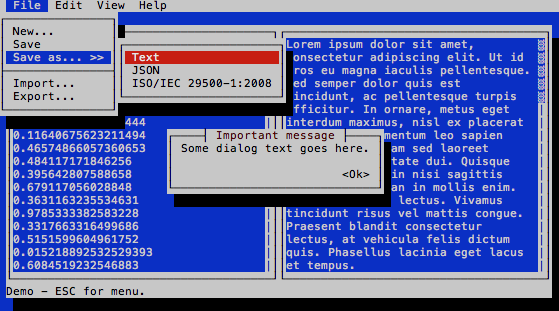

The following flow chart outlines the basic steps of the Tokio event

loop:

What happens when data arrives on a socket?

A useful exercise for understanding Tokio is to examine the steps that

occur within the event loop when data arrives on a socket. I was

surprised to discover that this ends up being a two-part process, with

each part requiring a separate epoll transaction in a

separate iteration of the event loop. The first part responds to a

socket becoming read-ready (i.e., a Mio event with an even-numbered

token greater than one for spawned tasks, or TOKEN_FUTURE

for the main task) by sending a notification to the task which is

interested in the socket. The second part handles the notification

(i.e., a Mio event with an odd-numbered token greater than one) by

polling the task and its associated future. We'll consider the steps in

a scenario where a spawned future is reading from a

UdpSocket on a Linux system, from the top of the Tokio

event loop, assuming that a previous poll of the future resulted in a

recv_from() returning a WouldBlock error.

The Tokio event loop calls mio::Poll::poll(), which in turn

(on Linux) calls epoll_wait(), which blocks until some

readiness change event occurs on one of the monitored file descriptors.

When this happens, epoll_wait() returns an array of

epoll_event structs describing what has occurred, which are

translated by Mio into mio::Events and returned to Tokio.

(On Linux, this translation should be zero-cost, since

mio::Events is just a single-tuple struct of a

epoll_event array.) In our case, assume the only event in

the array is indicating read readiness on the socket. Because the event

token is even and greater than one, Tokio interprets this as an I/O

event, and looks up the details in the corresponding element of

Slab<ScheduledIo>, which contains information on any

tasks interested in read and write readiness for this socket. Tokio

then notifies the reader task which, by way of the

MySetReadiness glue described earlier, calls Mio's

set_readiness(). Mio handles this non-system event by

adding the event details to its readiness queue, and writing a single

0x01 byte to the readiness pipe.

After the Tokio event loop moves to the next iteration, it once again

polls Mio, which calls epoll_wait(), which this time

returns a read readiness event occurring on Mio's readiness pipe. Mio

reads the 0x01 which was previously written to the pipe,

dequeues the non-system event details from the readiness queue, and

returns the event to Tokio. Because the event token is odd and greater

than one, Tokio interprets this as a task notification event, and looks

up the details in the corresponding element of

Slab<ScheduledTask>, which contains the task's

original Spawn object returned from spawn().

Tokio polls the task and its future via poll_future_notify(). The future may then read data from

the socket until it gets a WouldBlock error.

This two-iteration approach involving a pipe write and read may add a little

overhead when compared to other asynchronous I/O event loops. In

a single-threaded program, it is weird to look at the

strace and see a thread use a pipe to communicate with

itself:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 91011

|

pipe2([4, 5], O_NONBLOCK|O_CLOEXEC) = 0

...

epoll_wait(3, [{EPOLLIN|EPOLLOUT, {u32=14, u64=14}}], 1024, -1) = 1

write(5, "\1", 1) = 1

epoll_wait(3, [{EPOLLIN, {u32=4294967295, u64=18446744073709551615}}], 1024, 0) = 1

read(4, "\1", 128) = 1

read(4, 0x7ffce1140f58, 128) = -1 EAGAIN (Resource temporarily unavailable)

recvfrom(12, "hello\n", 1024, 0, {sa_family=AF_INET, sin_port=htons(43106), sin_addr=inet_addr("127.0.0.1")}, [16]) = 6

recvfrom(12, 0x7f576621c800, 1024, 0, 0x7ffce1140070, 0x7ffce114011c) = -1 EAGAIN (Resource temporarily unavailable)

epoll_wait(3, [], 1024, 0) = 0

epoll_wait(3, 0x7f5765b24000, 1024, -1) = -1 EINTR (Interrupted system call)

|

Mio uses this pipe scheme to support the general case where

set_readiness() may be called from other threads, and

perhaps it also has some benefits in forcing the fair scheduling of

events and maintaining a layer of indirection between futures and I/O.

Lessons learned: Combining futures vs. spawning futures

When I first started exploring Tokio, I wrote a small program to listen

for incoming data on several different UDP sockets. I created ten

instances of a socket-reading future, each of them listening on a

different port number. I naively joined them all into a single future

with join_all(), passed the combined future to

Core::run(), and was surprised to discover that every

future was being polled whenever a single packet arrived. Also somewhat

surprising was that tokio_core::net::UdpSocket::recv_from()

(and its underlying PollEvented) was smart enough to avoid actually calling the

operating system's recvfrom() on sockets that had not been

flagged as read-ready in a prior Mio poll. The strace,

reflecting a debug println!() in my future's

poll(), looked something like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9101112131415161718192021

|

epoll_wait(3, [{EPOLLIN|EPOLLOUT, {u32=14, u64=14}}], 1024, -1) = 1

write(5, "\1", 1) = 1

epoll_wait(3, [{EPOLLIN, {u32=4294967295, u64=18446744073709551615}}], 1024, 0) = 1

read(4, "\1", 128) = 1

read(4, 0x7ffc183129d8, 128) = -1 EAGAIN (Resource temporarily unavailable)

write(1, "UdpServer::poll()...\n", 21) = 21

write(1, "UdpServer::poll()...\n", 21) = 21

write(1, "UdpServer::poll()...\n", 21) = 21

write(1, "UdpServer::poll()...\n", 21) = 21

write(1, "UdpServer::poll()...\n", 21) = 21

write(1, "UdpServer::poll()...\n", 21) = 21

write(1, "UdpServer::poll()...\n", 21) = 21

recvfrom(12, "hello\n", 1024, 0, {sa_family=AF_INET, sin_port=htons(43106), sin_addr=inet_addr("127.0.0.1")}, [16]) = 6

getsockname(12, {sa_family=AF_INET, sin_port=htons(2006), sin_addr=inet_addr("127.0.0.1")}, [16]) = 0

write(1, "recv 6 bytes from 127.0.0.1:43106 at 127.0.0.1:2006\n", 52) = 52

recvfrom(12, 0x7f2a11c1c400, 1024, 0, 0x7ffc18312ba0, 0x7ffc18312c4c) = -1 EAGAIN (Resource temporarily unavailable)

write(1, "UdpServer::poll()...\n", 21) = 21

write(1, "UdpServer::poll()...\n", 21) = 21

write(1, "UdpServer::poll()...\n", 21) = 21

epoll_wait(3, [], 1024, 0) = 0

epoll_wait(3, 0x7f2a11c36000, 1024, -1) = ...

|

Since the concrete internal workings of Tokio and futures were somewhat

opaque to me, I suppose I hoped there was some magic routing happening

behind the scenes that would only poll the required futures. Of course,

armed with a better understanding of Tokio, it's obvious that my program

was using futures like this:

This actually works fine, but is not optimal — especially if you have a

lot of sockets. Because notifications happen at the task level, any

notification arranged in any of the green boxes above will cause the

main task to be notified. It will poll its FromAll future,

which itself will poll each of its children. What I really need is a

simple main future that uses Handle::spawn() to launch each

of the other futures in their own tasks, resulting in an arrangement

like this:

When any future arranges a notification, it will cause only the future's

specific task to be notified, and only that future will be polled.

(Recall that "arranging a notification" happens automatically when

tokio_core::net::UdpSocket::recv_from() receives

WouldBlock from its underlying

mio::net::UdpSocket::recv_from() call.) Future combinators

are powerful tools for describing protocol flow that would otherwise be

implemented in hand-rolled state machines, but it's important to

understand where your design may need to support separate tasks that

can make progress independently and concurrently.

Final thoughts

Studying the source code of Tokio, Mio, and futures has really helped

solidify my comprehension of Tokio, and validates my strategy of

clarifying abstractions through the understanding of their concrete

implementations. This approach could pose a danger of only learning

narrow use cases for the abstractions, so we must consciously consider

the concretes as only being examples that shed light on the general

cases. Reading the Tokio tutorials after studying the source code, I

find myself with a bit of a hindsight bias: Tokio makes sense, and

should have been easy to understand to begin with!

I still have a few remaining questions that I'll have to research some

other day:

-

Does Tokio deal with the starvation problem of edge triggering? I

suppose it could be handled within the future by limiting the number of

read/writes in a single

poll(). When the limit is reached,

the future could return early after explicitly notifying the current

task instead of relying on the implicit

"schedule-on-WouldBlock" behavior of the Tokio I/O source

types, thus allowing other tasks and futures a chance to make progress.

-

Does Tokio support any way of running the event loop itself on multiple

threads, instead of relying on finding opportunities to offload work to

worker threads to maximize use of processor cores?

UPDATE 2017-12-19: There is a

Reddit thread on r/rust discussing this post. Carl Lerche, author

of Mio, has posted some informative comments

here and

here. In addition to addressing the above questions, he notes that FuturesUnordered provides a means of combining futures such

that only the relevant child futures will be polled, thus avoiding

polling every future as join_all() would, with the tradeoff of additional

allocations.

Also, a future version of Tokio will be migrating away from the

mio::Registration scheme for notifying tasks, which could

streamline some of the steps described earlier.

UPDATE 2017-12-21: It looks like Hacker News also had a

discussion of this post.

UPDATE 2018-01-26: I created a

GitHub repository

for my Tokio example code.