Prologue

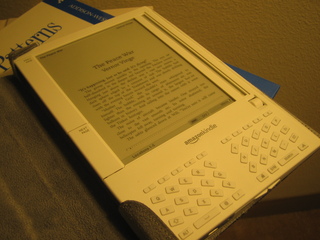

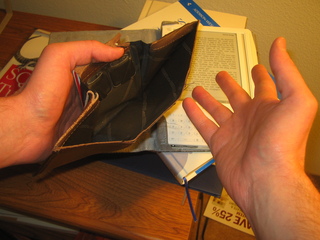

I broke down and bought a Kindle, the electronic book reader designed and sold by Amazon. I was somewhat interested in this device when it launched back in November, but Amazon sold out in five hours. Whether that's because of exceptional demand, or because Amazon only made eight, we'll never know. As a voting member of this year's World Science Fiction Convention, I recently received several books in electronic format for me to read and consider for the Hugo Award. (I tell people that I get to be a "superdelegate" for the big convention in Denver this fall.) As I spend way too many hours in front of a computer screen as it is, I figured this was as good an excuse as any to spring for an ebook reader. (Well, that, and an incurable love of gadgets.) It just so happened that Amazon had finally restocked the Kindle when I checked the web site on April 19th, so I decided to place the order. I selected the free two-day shipping, and my Kindle arrived a few days later.

I find Amazon's chosen name for this device to be a little disturbing. I'm sure they had in mind associations with "sparking an interest" or "igniting a revolution," but the first thing that came to my mind was visions of book burnings. I wonder if I should expect Fireman Montag from Fahrenheit 451 to burst into my apartment and incinerate my shelves of non-Amazon-compliant paper books. Amazon should have kept their development code name for the device, Fiona, which was inspired by Neal Stephenson's The Diamond Age.

Who would buy such a thing?

Instead of having to store and move printed editions of magazines that I'll never get around to reading (or even taking out of the plastic wrap), I can subscribe to electronic versions which can remain unread indefinitely without hassle.

The night before my Kindle arrived, I mentioned to a friend that I had ordered one. He just happened to find out about the Kindle earlier that day while browsing Amazon's web site, and wondered who on earth would buy such a thing. Now he knows.

Whenever I move, I'm reminded of one very important physical property of books. Books are heavy. I mean, sure, when you're turning a page, paper can seem light as a feather. Let me assure you that when you accumulate enough of these pages, the weight adds up. In addition to having mass, books also occupy space. Do I really need a wall full of bookshelves? What happens when I run out of walls? This is frustrating when my entire book collection, in electronic form, could probably fit on a single DVD.

Electronic books also offer the hope for broad availability of written works. There are many out-of-print books that may not have enough demand to justify reprinting, but could easily be made available electronically. Indeed, Jeff Bezos has expressed his vision for the Kindle as "every book ever printed in any language, all available in less than 60 seconds." I think that's easier said than done, but it's a noble goal and I wish him the best.

The Kindle is not without its naysayers. Steve Jobs says that the Kindle doesn't matter because no one reads anymore:

It doesn't matter how good or bad the product is, the fact is that people don't read anymore. Forty percent of the people in the U.S. read one book or less last year. The whole conception is flawed at the top because people don't read anymore.

While it's true that many people don't have the attention span for reading books these days, I think it's still possible to make good money from the segment of the population that remains actively literate. Barnes and Noble still seems to be able to pay their light bill. Amazon is still selling books. After all, consider the words commonly attributed to Mark Twain: "The man who does not read good books has no advantage over the man who can't read them."

Electronic paper

The Kindle's "electronic paper" display is the work of E Ink, a company whose flagship product of the same name can also be found in the Sony Reader. The E Ink display is radically different than the LCDs used in PDAs and cellphones. I first saw an E Ink display in 2004 at a Sony store in Tokyo, Japan. Among the gadgets available on display at the store was an early predecessor to the Sony Reader. When I saw this device, the paper-like display was so convincing that I thought I was looking at a dummy unit with a printed sheet of paper behind the screen. When I pressed a button and the content of the paper changed before my eyes, I was absolutely floored.

The E Ink display is the number one feature of the Kindle. Reading text on this display is much easier on the eyes than staring at a lit computer screen, and provides an experience much closer to reading a book. Unlike an LCD, bright light actually makes the image more readable, just like real paper, instead of washing it out. E Ink is also extremely frugal with battery power. No power is needed to maintain the image on the display -- only when you "flip a page." Because LCD screens are usually among the largest energy consumers in devices, the Kindle and other E Ink products can last a very long time before the battery needs to be recharged.

Electronic paper technology is still in its infancy, though, and there are some important drawbacks to consider, especially if you are accustomed to using devices with traditional LCD displays. The biggest drawback is the refresh rate. While the LCD screen in your notebook may repaint its image 60 times a second to deliver smooth animation and immediate feedback to the user, the E Ink display requires a noticeable delay to change anything on the screen. (More about this in "Usability," below.)

When you flip a page while reading, the Kindle momentarily clears the screen with a sort of "black flash" that some people find annoying. These people are of the opinion that it disturbs the continuity of reading. I've noticed that in a few cases where dialog boxes do not perform this flash, it's possible to look closely and see a very faint residual image of the previous screen contents. Therefore, I assume the black flash is necessary to avoid this residual image problem. It doesn't bother me, personally. I stopped noticing it after a few minutes of use.

Besides the slow refresh time and the dreaded black flash, the drawbacks are quite minor. The plastic screen surface seems to reflect a small amount of glare from light sources. The glare is greater than the page of a book, but far less than the glare on PDAs or cellphones. Also, I wouldn't mind if the display had a bit more resolution and contrast.

The E Ink display is both the Kindle's greatest asset and its primary limitation. In spite of the downsides, E Ink does deliver an incredibly beautiful display for reading text. It's important to understand and appreciate the trade-off. If you're not in any hurry to buy an ebook reader, you can probably hold off for a couple of years and get a much improved display at a lower cost.

Usability

When the Kindle was launched in November, the reaction to its design was almost universal: This thing is ugly. These days, people expect sleek designs such as found on the iPhone, and Amazon built a device that looks like it fell through a time warp from the 80's, and wouldn't look terribly out of place in Flash Gordon or Buck Rogers. I'm willing to cut them some slack for this first release, though, and not judge a book by its cover. Fortunately, it turns out that most books don't require much interaction -- as long as "next page" works, the usability concerns are minimal.

Much of the design of the Kindle exists to work around the limitations of the E Ink display. This has led to a somewhat unconventional interface which avoids screen updates like the plague. For instance, to select menu options and text, the Kindle provides a strange secondary display in the form of a thin vertical stripe to the right of the screen. They call this a "cursor bar," and it works by activating small silver squares which correspond to a selected area of the main screen. (For the life of me, I still haven't figured out what sort of display technology this is. Silver squares that appear and disappear? Maybe this thing really did come from Flash Gordon!) A thumb wheel is provided below the cursor bar to move the cursor. As you may have guessed by now, the Kindle does not have a touch screen.

E Ink's slow refresh time is the primary limitation of the Kindle, giving the device a somewhat sluggish feel while navigating pages and interacting with features. An average page flip takes about 1.5 seconds. I've found that the extent to which this a problem varies greatly depending on what sort of reading material is being consumed. The more you need to flip through random pages, the more you will be frustrated by this slowness. When my Kindle arrived, I read several short stories on it. The Kindle excels at this sort of content, and the delay was not an issue at all. I've started reading a complex novel, and I occasionally feel the need to flip through previous pages to refresh my memory about certain minor characters. This is not a pleasant activity on the Kindle. I would expect reference and technical material such as textbooks to be most negatively impacted by the slowness. (Sorry college students, you're going to have to carry around a backpack full of books for a while longer.) It is a small consolation that you can flip several pages at once by pressing the "next page" and "prev page" buttons multiple times in rapid succession. Perhaps I should explore the Kindle's search features some day.

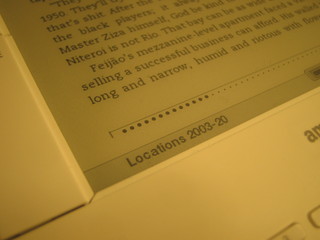

Because page numbers are not very useful for electronic books where the text size can be changed by the user, the Kindle uses the abstract notion of "location numbers" for referencing positions in the text. For example, I'm about a quarter of the way through a novel and "Locations 2003-20" appears at the bottom of the screen to let me know which "locations" are being displayed on the current page. In lieu of real page numbers, this is probably the best that can be done, although I don't expect to see people using locations when citing references anytime soon.

Other minor nitpicks I have with the device are the screensaver, which seems too eager to activate when I'm taking too long to read a page, and the main menu for selecting content, which shows all titles on the device with no hierarchy. I could imagine this list of titles could grow to be quite large, and be cumbersome to browse.

It is inevitable that people will compare the Kindle to more responsive and feature-rich devices such as PDAs and tablet computers. I don't think this comparison is very fair, but I understand why people value the characteristics of those sorts of devices. Today, in 2008, you can have either a snappy, rich user interface, or a beautiful paper-like screen. I hope the technology advances enough to eliminate this compromise, so users can truly have it all.

Features

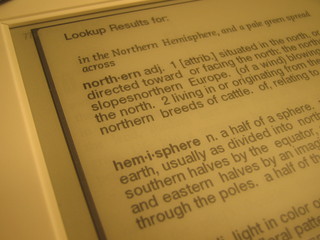

You can read the full feature list of the Kindle at Amazon's web site, but a couple of features are noteworthy enough to mention here. One surprisingly useful feature that I didn't know about when ordering is the online dictionary. While I'm reading, if I come across a word that I'm not familiar with, I can select it and immediately retrieve the definition from The New Oxford American Dictionary. This has come in handy quite often.

The Kindle is unique among electronic book readers for its wireless connectivity through Sprint's EV-DO network. The service, which Amazon calls "Whispernet," is used to connect to the Amazon store and download purchased books. There are no special charges for this service, other than the cost of the content you purchase. The Kindle also uses the wireless service to provide free access to Wikipedia. An experimental web browser also allows you to access simple, text-oriented web sites, but this "Basic Web" is not an advertised feature and is not guaranteed to be available forever.

Content

The biggest worry people have with acquiring content for the Kindle is the Digital Rights Management (DRM) copy protection found on works purchased from Amazon's Kindle Store. The concern is that if Amazon decides to stop supporting the Kindle, your investment in books may go up in smoke -- especially if your Kindle stops working some day. In contrast, a traditional printed book is likely to last a lifetime, even if the publisher goes out of business. While it might seem far-fetched that a major company like Amazon would stop supporting customers' purchases, it is not without precedent. For instance, Microsoft recently announced that it is discontinuing support for purchases from the MSN Music Store, which uses the ironically named PlaysForSure DRM protection. If customers want to play their music after the cutoff date, they must keep the same computer for the rest of their lives, and never reinstall or upgrade the operating system. It's no wonder that many customers are skeptical about allowing their investment to rely upon the continued goodwill and support of the retailer.

I'm probably going to dabble a little with the Kindle Store while I decide where my comfort level is with DRM encrypted content. Using the Kindle's built-in support for browsing the Kindle Store, I picked up Vernor Vinge's The Peace War, and it was delivered wirelessly to my Kindle. The process seemed to work smoothly and as advertised.

It is important to note that the Kindle is not restricted to viewing encrypted content obtained from the Kindle Store. The Kindle can directly view plain text (.txt), HTML, and unencrypted Mobipocket files that you transfer to the device from your computer. Using conversion software (or Amazon's convert-by-email service), you can view many additional formats on the Kindle, such as RTF, Word, etc. Mobipocket, a well-established ebook provider, was acquired by Amazon in 2005 and the company's ebook format is the native format for content on the Kindle. Encrypted Mobipocket files will only work on the Kindle if you bought them from the Kindle Store. However, any unencrypted Mobipocket files you may already have should work fine.

Many people have complained about the Kindle's lack of advertised PDF support. I think these people fail to truly understand the nature of PDF documents. PDF documents are stored in a strongly page-oriented fashion, ready to be sent to the printer. Unlike HTML, RTF, or Microsoft Word files, there is no concept of paragraphs or flowed text (word wrapping). Displaying a PDF document containing 8.5"x11" or A4 pages on a smaller screen with variable font sizes is not easy without applying some intelligence to turn the fixed-position lines of text back into paragraphs so they can be word-wrapped. Turning PDF content back into flowed text that can be displayed well on an ebook reader is akin to unscrambling an egg. Despite the challenges, however, it is quite possible to view PDF content on the Kindle. I use the freely available Mobipocket Creator software to convert documents into Mobipocket format for reading on the Kindle, and it will indeed perform best-effort conversion of PDF files. The PDF content that I've converted has been very simple, and it is viewable quite well on the Kindle. Anything more than the simplest of PDF files is likely to not convert well, though, so it is strongly recommended to only use PDF source material as a last resort.

My favorite source of ebook material is the Fictionwise web site. Fictionwise is an established ebook retailer, and many of the books and periodicals they carry are unencrypted so I don't have to worry about my purchases going bad. The unencrypted content is labeled as "MultiFormat." I've already spent far more money at Fictionwise than I have at the Kindle store.

Cost

Amazon is currently selling the Kindle for $399.00, which is quite a hefty sum for most people's book budgets. At that price, you could instead buy 57 paperback books at $7 a pop, and be reading happily for quite some time. This price tag is a bit much, and it will probably deter most people from jumping into the wild world of ebooks.

Undoubtedly, the $399.00 price includes a built-in "early adopter penalty." With so much room for improvement and possible technological advances in electronic paper, I think that electronic book readers are bound to get a lot better and cheaper over the next few years. In some ways, the Kindle reminds me of the first digital camera I bought, back in 1996. It was an Apple QuickTake 150 that could take a whopping twenty or so 640x480 (0.3 megapixel) photos before running out of memory and battery, all for the low price of $700. It was brilliant -- I no longer needed to have film developed and scanned to put my pictures on the web. About nine months after I made the purchase, the digital camera market exploded with a wide selection of models that were vastly superior for half the price, and I was left with an obsolete relic. Perhaps in a year or two I'll feel the same way about this first-generation Kindle.

Epilogue

The Amazon Kindle is generally a fine device for reading books, and I've enjoyed mine quite a bit so far. No longer will I have to face the possibility of running out of reading material on long trips. The Kindle is far from perfect, however, and unless you're a gadget freak like me, you might want to hold off on buying one of these for a couple of years. The technology is still in its infancy, but it has a very promising future. If you are a gadget freak like me and you're considering buying the Kindle, well... c'mon, you know you wanna!

posted at 2008-05-02 03:50:25 US/Mountain

by David Simmons

tags: gadgets review ebooks kindle

permalink

comments